Originally, I was resistant to learning TypeScript because I wasn’t comfortable with strongly typed languages and I really tried to avoid writing any more code than I had to. But this is the situation where writing a little more code upfront will pay big dividends as your project grows.

Benefits

The biggest benefit is actually the tooling you get in your IDE like VS Code. When you use type annotations or work with strongly typed libraries, your code will be documented in the IDE so you really don’t have to refer back to online documentation for the libraries that you use. In addition, the compiler can catch bugs in advance, which is a far more efficient way to refactor code.

Another cool benefit of TypeScript is that there’s virtually no learning curve if you know JavaScript. That’s because it’s a superset of JavaScript. So any valid JS code is also valid in TypeScript. You can learn it incrementally as you go. And it also allows us to write code with future JavaScript features without having to worry about whether or not this code will be supported in our environment because we can transpile it to multiple JavaScript flavors.

Install TypeScript

Now that you know TypeScript is awesome, let’s go ahead and get started. The first thing you want to do is install TypeScript globally with NPM. Doing this will give you access to the tsc command which will run the TypeScript compiler.

npm i -g typescriptCompile TypeScript to JavaScript

The first thing we’ll do is create an index.ts file. TypeScript on its own can’t run anywhere. It won’t work in the browser or Node.js or anything like that. What we do is use the TypeScript compiler to convert TypeScript code to vanilla JavaScript.

Let’s start by writing some plain JavaScript in our TypeScript file and then compile it.

console.log("hello world");Go to the command line and run tsc index.ts.

You’ll notice it creates an index.js file that’s our actual JavaScript code which we can run in the browser or Node. And because we just wrote plain JavaScript, the code is identical to what’s in the index.ts file.

console.log("hello world");By default, TypeScript will compile to ES3 which doesn’t support async/await. So let’s see what happens when we write an async function in our .ts file and then compile it.

async function hello() { return "world";}You’ll notice here that our code gets transpiled to this crazy-looking JavaScript so we can use async/await in our main TypeScript code.

var __awaiter = (this && this.__awaiter) || function (thisArg, _arguments, P, generator) { function adopt(value) { return value instanceof P ? value : new P(function (resolve) { resolve(value); }); } return new (P || (P = Promise))(function (resolve, reject) { function fulfilled(value) { try { step(generator.next(value)); } catch (e) { reject(e); } } function rejected(value) { try { step(generator["throw"](value)); } catch (e) { reject(e); } } function step(result) { result.done ? resolve(result.value) : adopt(result.value).then(fulfilled, rejected); } step((generator = generator.apply(thisArg, _arguments || [])).next()); }); };

// +33 linesCompiler

The compiler is basically very sophisticated. There’s a ton of different options that you can pass to customize its behavior. You could pass the options from the command line but the standard way to do it is to create a tsconfig.json which will automatically get picked up when you run the tsc command.

The tsconfig.json can be pretty overwhelming at first but there are usually only a few options that you have to think about for the most part.

target

The first one is target, and this is the flavor of JavaScript that your code will be compiled to. So if we set target to esnext and then run tsc, you’ll see that it compiles our code with async/await natively. It’s targeting the latest version of JavaScript which supports that syntax.

{ "compilerOptions": { "target": "esnext" }}watch

Another option that we want to set right away is "watch": true which will just recompile our code every time we save the file. It will save us from rerunning the tsc command after every change.

{ "compilerOptions": { "target": "esnext", "watch": true }}lib

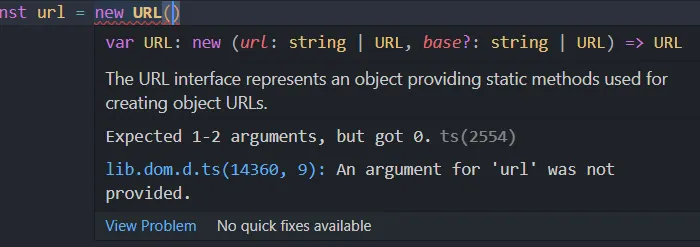

The next option we will look at is lib which allows us to automatically include typings for certain environments such as the DOM or ES2017. So if you’re building a web application you’d want to include that DOM library which allows TypeScript to compile your code with all the native DOM classes without any compilation error.

{ "compilerOptions": { "target": "es3", "watch": true, "lib": ["dom", "es2017"] }}For example, if we go back to our code, we can use the URL class which is part of the DOM and we’ll get autocomplete and IntelliSense on this class. So this is where the incredible tooling of TypeScript starts to come in. If we hover over the class we have integrated documentation as well as an error message telling us exactly why this code won’t run.

Type

Now that we know how the TypeScript compiler works, let’s go ahead and write some code that uses type annotations. There are two ways you can strongly type your code: implicitly or explicitly.

Implicit Type

Let’s say we have a variable that should be a number. If we assign the value to this variable when it’s declared, its type will automatically be inferred.

let lucky = 23; // lucky will have number typeThen if we try to assign a string value to this variable it’s going to give us an error because a string is not assignable to number. If this code were vanilla JavaScript we wouldn’t catch this bug until we actually run this code somewhere. But with TypeScript we know about it right away.

let lucky = 23; // lucky will have number typelucky = "23"; // error because we can't assign string value to number variableUnlike languages like C# or Java, we can actually opt out of the type system by annotating our variable with any.

let lucky: any = 23; // lucky will accept all types of valuelucky = "23"; // including stringThis just means that this variable can be assigned any value and the compiler won’t type check it. Ideally you want to avoid doing things like this when possible, but it does give TypeScript a ton of flexibility.

Explicit Type

In the above example we gave our variable an implicit number type, but what if we don’t have a value to assign to it upfront? If we don’t add any type annotations, it’s going to be inferred as an any type, so we can assign both a string and number to it. If we want to annotate it with a type, we can just write a colon followed by number which is one of the built-in primitive types in JavaScript. When we do that, we get an error under the string value because we can’t assign it as that type.

let lucky: number; // lucky type will be number

lucky = "23"; // error assigning string valuelucky = 23; // no errorDefine Custom Types

So we’ve looked at some of the built-in types in JavaScript. But you can also create your own types. First you’ll give the type a name which is typically in PascalCase.

type Style = string;Then we can declare a variable that’s annotated with this Style type and then we’ll get feedback for this custom type instead of just regular string.

type Style = string;let font: Style;Let’s say our style type can only be bold or italic. We can create a union type by separating them with a pipe. And now we can only assign this variable to these two specific values. And we’re not limited to just strings; we could even extend this custom type with a number.

type Style = "bold" | "italic" | 23;let font: Style;Interface

So that’s pretty cool, but more often, you’ll be strongly typing objects that have multiple properties with different types. Let’s imagine we have two objects and we want to enforce that this object shape has a first and last name with string types.

const person1 = { first: "Harry", last: "Maguire",};

const person2 = { first: "Usain", last: "Bolt", fast: true,};Composing objects or class instances that don’t have the correct shape is an easy way to create bugs. But with TypeScript we can enforce the shape of an object with an interface. If we know the shape of an object would be the same, then we can define an interface that defines the type of each property.

interface Person { first: string; last: string;}Now we can use this interface to strongly type this object directly or we could use it as the return value from a function, argument, or anywhere else in our code.

interface Person { first: string; last: string;}

const person1: Person = { first: "Harry", last: "Maguire",};

const person2 = { first: "Usain", last: "Bolt", fast: true,};Now sometimes an interface like this can be too restrictive. You can maintain the required properties and then add additional properties by creating a key with a type of string with a value type of any. So now a first and last name will be required, but you can also add any additional property that you want to this object.

interface Person { first: string; last: string; [key: string]: any;}

const person1: Person = { first: "Harry", last: "Maguire",};

const person2 = { first: "Usain", last: "Bolt", fast: true,};Function

Now let’s go ahead and switch to functions. Strong typing in a function can be a little more complex because you have types for arguments and also the return value. Here we just have a plain JavaScript function without any types.

function pow(x, y) { return Math.pow(x, y);}Then we could add string values as the arguments and we wouldn’t get any error from the compiler. But obviously this function is going to fail if we try to pass it any non-number value.

function pow(x, y) { return Math.pow(x, y);}

pow("23", "foo");You can annotate arguments the same way we do with variables. That will ensure only numbers can be passed to this function.

function pow(x: number, y: number) { return Math.pow(x, y);}

pow(5, 10);So the function implicitly has a number return value because we’re using the native Math JavaScript library, but we can annotate a specific return value type after the parentheses and before the bracket. So if we set that type to a string you’ll see it’s underlined in red because it’s returning a number. To implement this function correctly we can call the toString() method.

function pow(x: number, y: number): string { return Math.pow(x, y).toString();}

pow(5, 10);In many cases you might have functions that don’t return a value or create some kind of side effect, in that case you can type your function return value to void.

The next thing we’ll look at is how to strongly type an array. We’ll start by creating an empty array then pushing different values to it with different types.

const arr = [];

arr.push(1);arr.push("23");arr.push(false);We can force this array to only have number types by using a number type followed by brackets, signifying that it’s an array. Now you can see we get an error every time we try to push a value that’s not a number.

const arr: number[] = [];

arr.push(1);arr.push("23"); // errorarr.push(false); // errorThis is especially useful when you’re working with an array of objects and you want to get some IntelliSense as you’re iterating over those objects.

TypeScript also opens the door to a new data structure called a tuple. Basically this is just a fixed-length array where each item in that array has its own type.

type MyList = [number, string, boolean];

const arr: MyList = [];

arr.push(1);arr.push("23");arr.push(false);You can make each item’s value optional by putting a question mark after the type. You can also use this question mark syntax in other places.

type MyList = [number?, string?, boolean];Generic

The last thing is TypeScript generics. You may run into situations where you want to use a type internally inside of a class or function. For example, here I have an Observable class that has an internal value that you can observe.

class Observable<T> { constructor(public value) {}}The T represents a variable type that we can pass in to strongly type this Observable’s internal value. This allows us to specify the internal type at some point in our code. For example, we have an Observable of a number or Person interface like below. Or we can also do this implicitly if we create a new Observable of a number, it’s going to implicitly have that internal number type.

class Observable<T> { constructor(public value: T) {}}

let x: Observable<number>;let y: Observable<Person>;let a = new Observable(23);More often than not, you’ll be using generics rather than creating them. But it’s definitely an important thing to know.

I’m gonna go ahead and wrap things up there. Hopefully this article gives you an idea of why TypeScript is so powerful, but we really only scratched the surface here. Don’t forget to check the official documentation to learn more about TypeScript features.